Robert Jenkin wrote:

After reading the 2007 New Zealand Book Award History prize-winning book Vaka Moana (2006, K.Howe ed.) and Atholl Anderson’s chapters of the 2015 Royal Society of New Zealand Science Book prize-winning book Tangata Whenua I think I understand that stages in the evolution of the shunting oceanic-lateen were first the double-sprit, next the oceanic-sprit, next and crucially the prop-masted oceanic-lateen, as used by Tonga in her ‘imperial’ period, which may have reached the Cook Islands from Tonga in or before the 11th century, and finally the shunting oceanic-lateen. This is the ‘flyer’ type, which so impressed visiting Europeans, first Magellan in Guam in 1521, then the Dutch in Batavia Java, in the 17th century and later the English and the French in northeast Polynesia in the 18th century. The shunting oceanic-lateen arguably out-performed any other sailing rig in the world, but in order to tack by ‘shunting’, waka that used it needed to be double-ended.

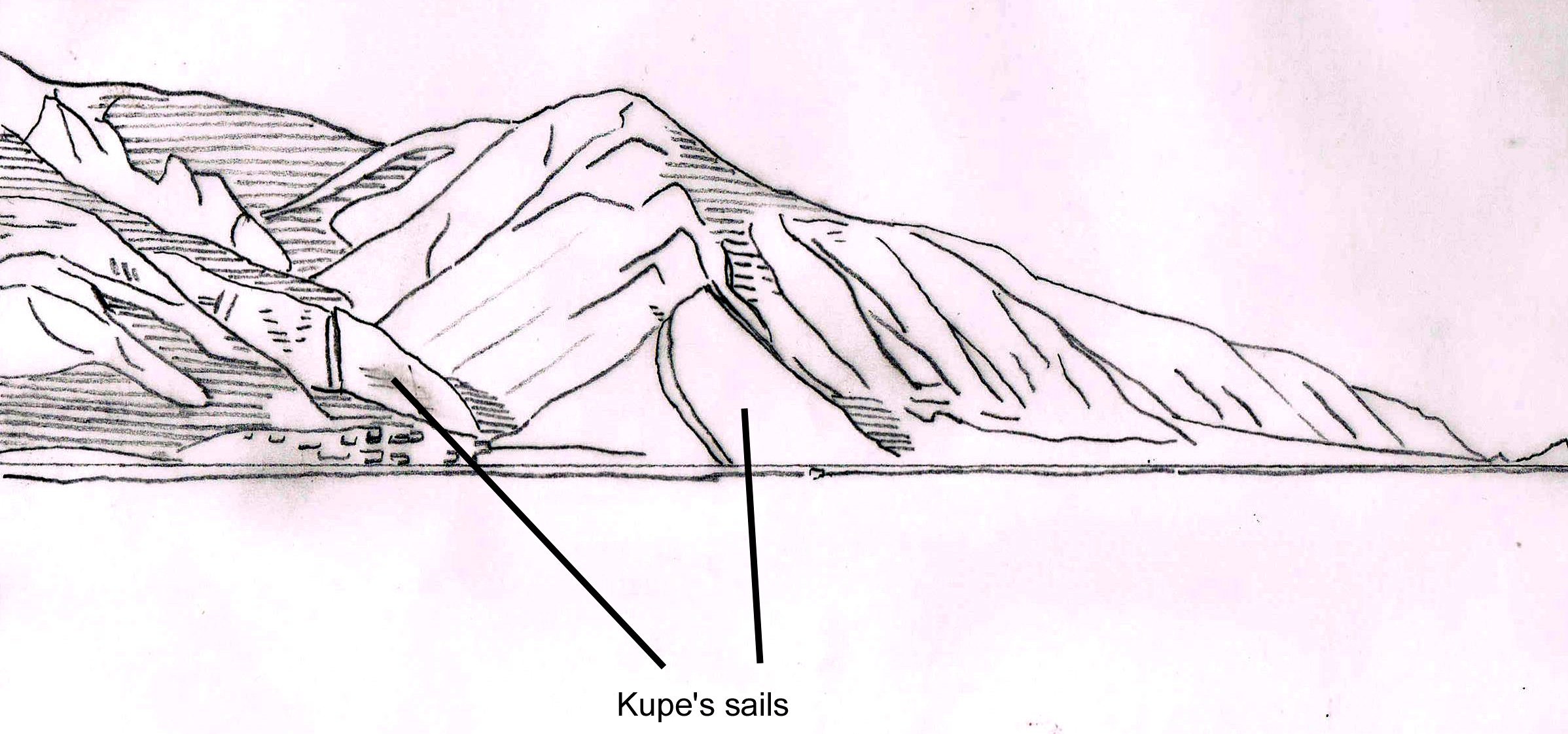

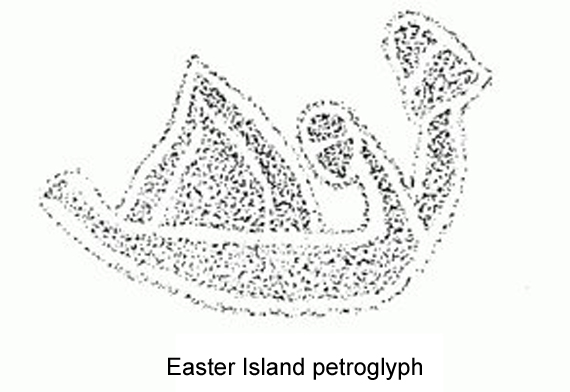

In order to to make return trips to South America, Easter Island, Hawaii and Aotearoa, East Polynesian voyaging waka had to sail fast, at least with and across the wind. The sail used on some of the voyaging canoes that came here in the thirteenth century could possibly have been the prop-masted oceanic-lateen, as indicated by the Wairarapa coast landforms called Kupe’s sails and also by an Easter Island petroglyph. This was also the sail first seen by Europeans on an open ocean voyaging canoe. The Schouten and le Maire expedition sighted, captured and eventually released a Tongan double hulled voyaging canoe with a complement of about 25 possibly on its way from Tonga to Samoa in 1616. Tonga and Samoa may have first developed prop-masted lateen sails centuries before, perhaps even before the 11th century. In that case East Polynesians would very possibly also have acquired them, perhaps through the Cook Islands, and used them in the the 12th and 13th centuries for their far-ranging trans-Pacific voyages.

In order to to make return trips to South America, Easter Island, Hawaii and Aotearoa, East Polynesian voyaging waka had to sail fast, at least with and across the wind. The sail used on some of the voyaging canoes that came here in the thirteenth century could possibly have been the prop-masted oceanic-lateen, as indicated by the Wairarapa coast landforms called Kupe’s sails and also by an Easter Island petroglyph. This was also the sail first seen by Europeans on an open ocean voyaging canoe. The Schouten and le Maire expedition sighted, captured and eventually released a Tongan double hulled voyaging canoe with a complement of about 25 possibly on its way from Tonga to Samoa in 1616. Tonga and Samoa may have first developed prop-masted lateen sails centuries before, perhaps even before the 11th century. In that case East Polynesians would very possibly also have acquired them, perhaps through the Cook Islands, and used them in the the 12th and 13th centuries for their far-ranging trans-Pacific voyages.