In 1996, in Making Peoples, Belich wrote that if Polynesian navigators could travel from some possible Hawaiki to New Zealand and then back again they were “in danger of becoming deified rather than merely superhuman”. Even the vikings, he observed, never managed “more than a thousand or so kilometres in one hop”. And he went on to say “repeated intercourse” between New Zealand and tropical Polynesia could safely be dismissed on current evidence because return voyages were “not very credible for New Zealand”. He left himself a bit of wriggle room though with this caveat: “It may be that the Great Fleet, or at least a Little Fleet, will strike back.” (pp.32-33).

In 2015 Atholl Anderson argued in Tangata Whenua that New Zealand’s Polynesian colonists had not come here in any such deliberate migration after prior two way voyages. Like Belich he considered that the waka and the sailing rigs available to them could not have made such return voyages and like Belich he pointed out that objects of New Zealand origin have not yet turned up at their likely starting points in Polynesia. So not a lot seemed to have changed in twenty years, except perhaps in our imaginations: one of the biggest movies to come out last year, Moana, focuses on Polynesian voyagers.

Two years ago I speculated in a thread here, Kupe’s sails, that sail-capable double-hulled waka using prop-masted oceanic-lateen sails may have been written of and drawn by Dutch in Golden Bay in 1642. Geoff Irwin’s reconstruction of the Anaweka Waka, part of which is now in Takaka, shows it rigged with what academic’s call an Oceanic Sprit.

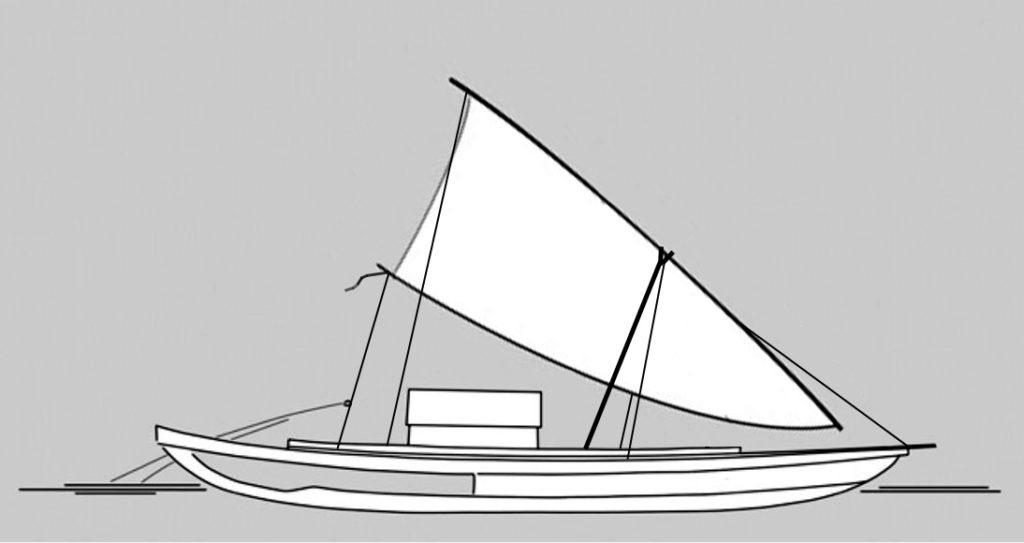

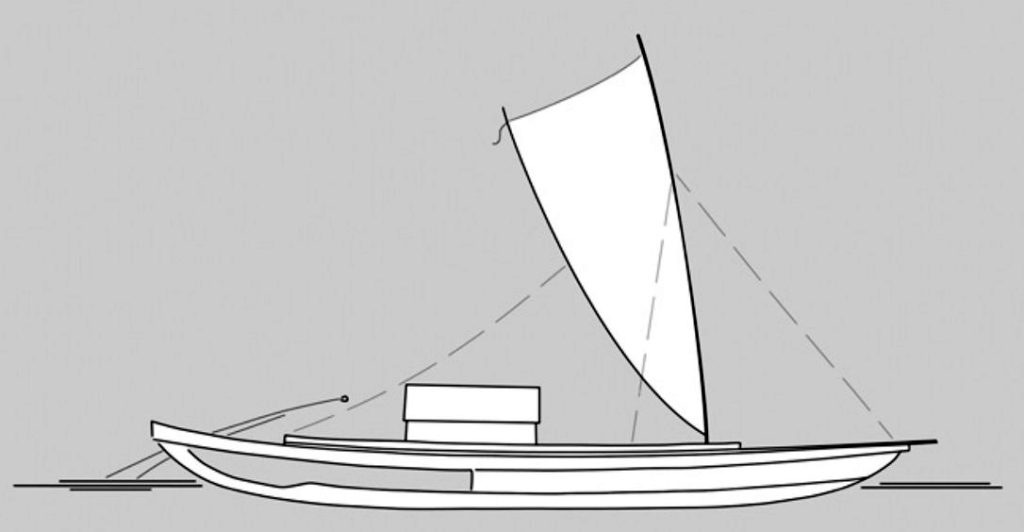

The Anaweka Waka is reportedly made of New Zealand Matai and was last used according to radiocarbon dating around 1400CE. I’ve wondered if such a waka, by the 15th century, might have been tongiaki rigged as shown below, its owners having learned this rig from Tongans in Samoa and the Cooks during a phase of two way voyaging that lasted from perhaps as early as the 12th until perhaps the outset of the 15th century.

This is because I think, as others do, that return voyages from here to the ‘Hawaiiki Zone’ were possible and even probable. New texts that bear on this have very recently become available.

This is because I think, as others do, that return voyages from here to the ‘Hawaiiki Zone’ were possible and even probable. New texts that bear on this have very recently become available.

One, out this year, is based on the remains of early waka in New Zealand. By Irwin, Johns and others, it is a ‘Review of Archaeological Māori Canoes (Waka)’ which ‘Reveals Changes in Sailing Technology and Maritime Communications in Aotearoa/New Zealand, AD 1300–1800’. Through time, it tells us there was a prevailing shift from multihulls to monohulls and general decline in the sailing performance of New Zealand waka. New types developed that were suited best for paddling and sailing downwind. But at first settlement, waka which sailed better were apparently predominant. This academic text is not yet free to read online. But I link here to two that are, and I investigate Moana, with its vastly greater audience.

An academic text published online less than two months ago is titled Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand. In this Walter et al fulfill that Belich prophesy that the Great Fleet hypothesis may yet strike back. Look into it, using the link above; I will return to it.

Another paper that I only read quite recently though it emerged in 2009 is called TRIANGULAR MEN ON ONE VERY LONG VOYAGE: THE CONTEXT AND IMPLICATIONS OF A HAWAIIAN-STYLE PETROGLYPH SITE IN THE POLYNESIAN KINGDOM OF TONGA. I like the way this partially enlarges our East Polynesian triangle, the one in which New Zealand, far to the southwest, got settled last. It does this through a close examination of anthropomorphs, carved human figures who do really look triangular. That surfer, carved into a rocky outcrop on a Tongan beach apparently around the 14th century, is food for thought.

Triangular men and women in Hawaii and the Tongan archipelago. Figures i and k are seen as surfers, f and h are turtles, e and g are transformational, either humans changing to turtle form or turtles to human. Compare these with the turtle on the Anaweka waka.

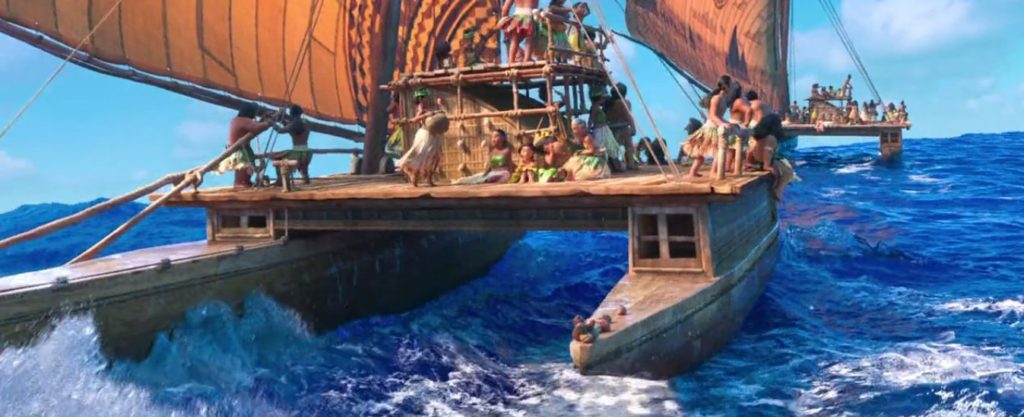

Disney’s Moana may determine how the voyaging canoes of Polynesians are perceived by most people for years to come. And that might not be such a bad thing; it’s a good movie in lots of ways and I believe its images and words are worth considering alongside those of the two papers mentioned in the two preceding paragraphs.

“We read the wind and the sky

When the sun is high

We sail the length of the seas

On the ocean breeze

At night we name every star

We know where we are

We know who we are, who we are

Aue, aue,

We set a course to find

A brand new island everywhere that we roam

Aue, aue,

We keep our island in our mind

And when it’s time to find home

We know the way”

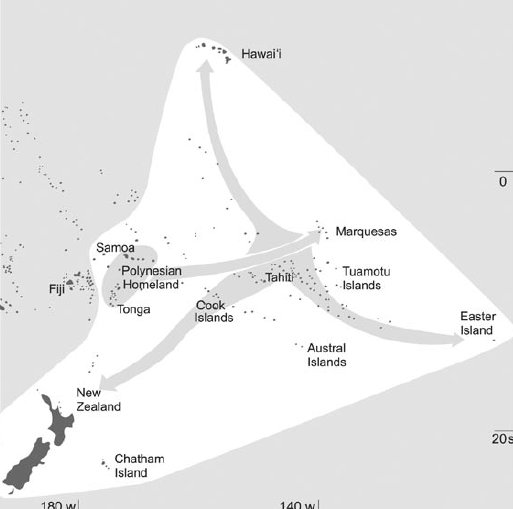

Opetaia Tavita Foa’i, who helped to write this song, grew up in Samoa and Tokelau. A lot of modern Polynesians don’t see European sea-farers like the vikings as the best early open ocean voyagers, they see their own peoples that way, and may be justified in doing so, since while the vikings hugged the icy north Atlantic and explored the waterways of Eastern Europe, East Polynesians found and occupied Hawaii, Easter Island and New Zealand.

This plate from Triangular Men shows us the scale of that, and like the vikings those who made such voyages needed good ships.

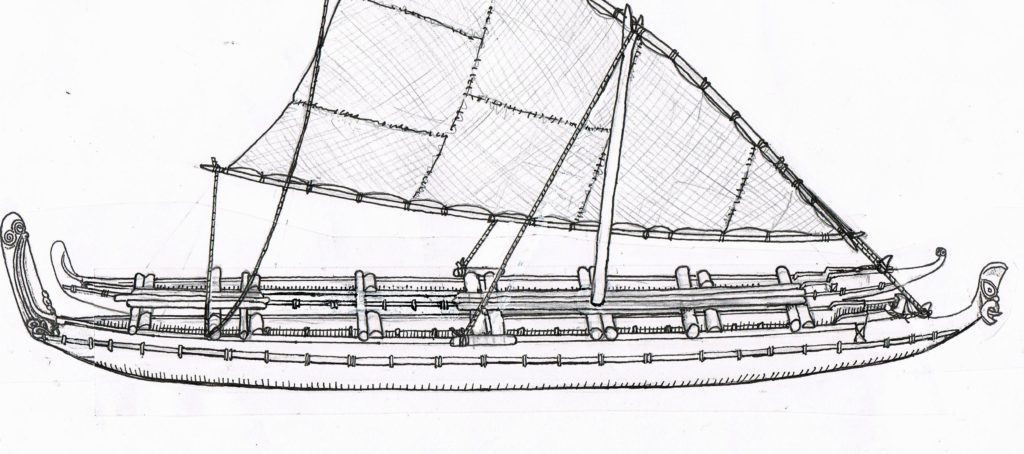

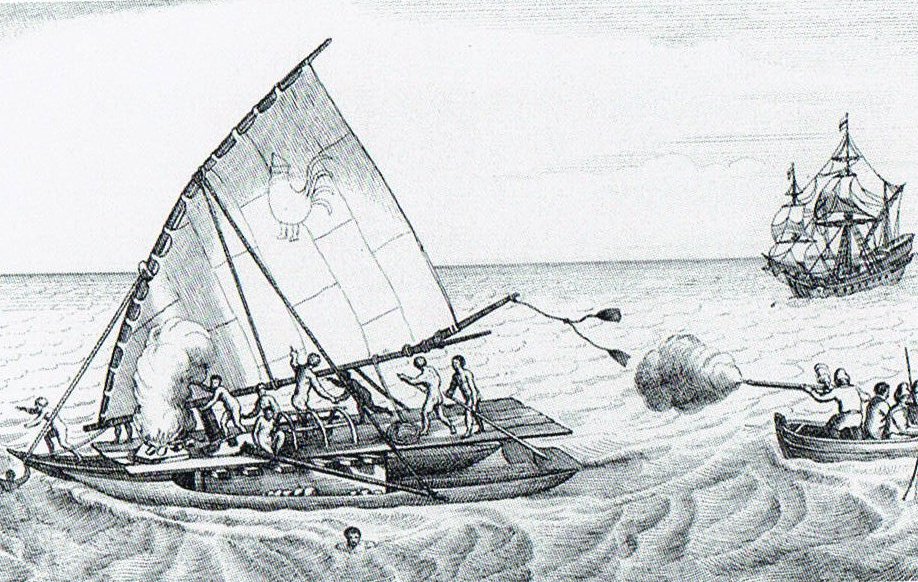

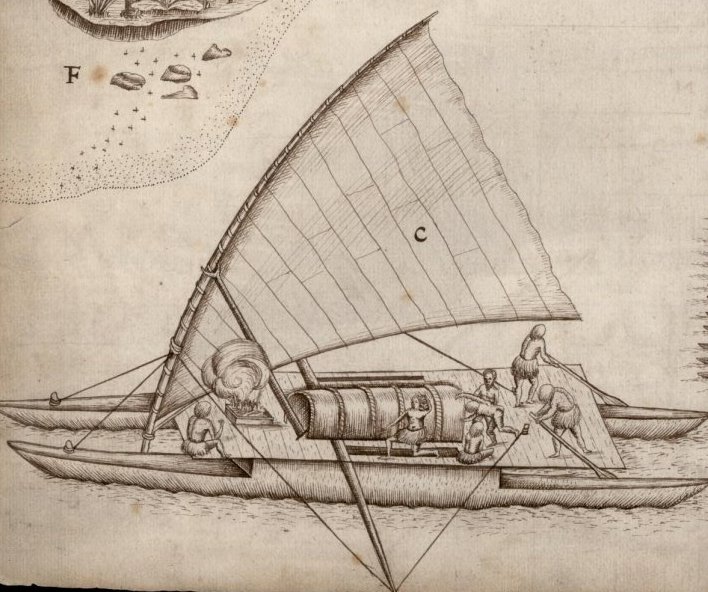

The waka in Moana’s fleet have oceanic lateen looking sails, not oceanic spritsails. But are they tongiaki rigged? The tongiaki rigs below were drawn by two Dutch artists, one on Eendracht in 1616 and one on Heemskerck in 1643.

The model, clearly partly based on the Dutch images, resembles voyaging canoes seen in Moana in at least some ways.

As shown here they have fork topped masts; true oceanic lateen sails were hauled up to meet such forks and held down at the front against the prow of the main hull. This differs from the tongiaki where the crutch mast fork cradles the upper spar and the front of the sail floats between two prows of equal size. As reconstructed in Te Papa’s model the crutch mast appears to remain fixed within one hull, though I can’t work out how the sail can be raised and lowered if thats the case.

As shown here they have fork topped masts; true oceanic lateen sails were hauled up to meet such forks and held down at the front against the prow of the main hull. This differs from the tongiaki where the crutch mast fork cradles the upper spar and the front of the sail floats between two prows of equal size. As reconstructed in Te Papa’s model the crutch mast appears to remain fixed within one hull, though I can’t work out how the sail can be raised and lowered if thats the case.

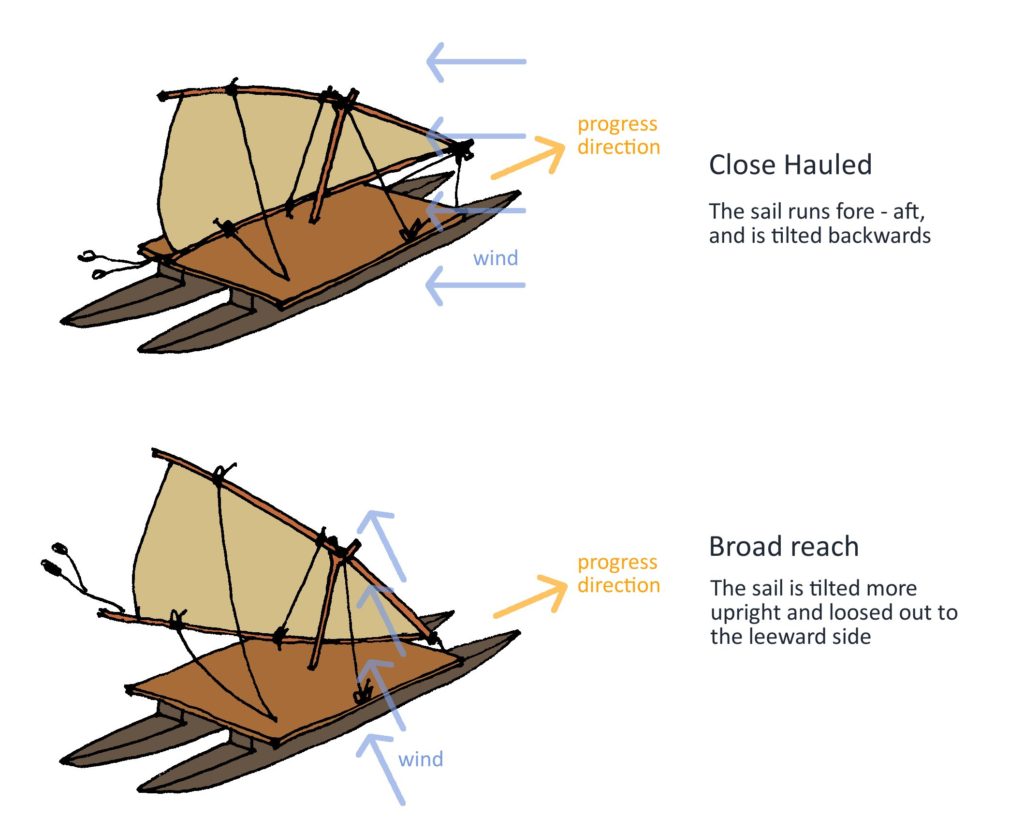

As Dave Horry and I interpret the crutch mast it was simply lifted into place on the top deck, and so could change its angle as the sail trim changed.

Moana’s largest waka have raised decks on widely spaced hulls but their masts seem permanently steppd inside one larger hull.

Moana’s largest waka have raised decks on widely spaced hulls but their masts seem permanently steppd inside one larger hull.

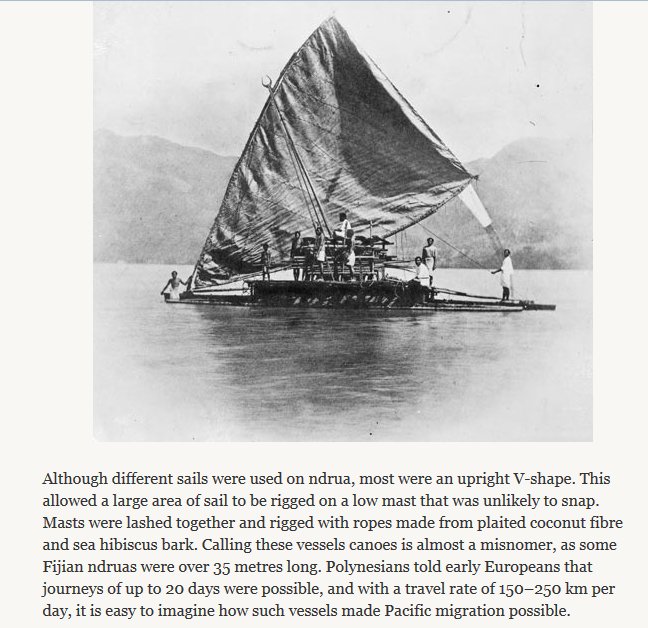

A rig like this seems close to that of the Fijian ndrua, (double) or camakau (outrigger) canoes of the 19th century. These had true oceanic lateen rigs, and so were shunted through the wind, not tacked across it. The fork topped masts, which pivoted towards whichever end became the front, also allowed the sail to pivot round the mast

A rig like this seems close to that of the Fijian ndrua, (double) or camakau (outrigger) canoes of the 19th century. These had true oceanic lateen rigs, and so were shunted through the wind, not tacked across it. The fork topped masts, which pivoted towards whichever end became the front, also allowed the sail to pivot round the mast

Such lateen rigs did not exist in the ‘Hawaiiki Zone’ before the 15th century. But tongiaki rigs, their ancient predecessors, evidently did. So if we saw Moana’s voyaging canoes as tongiaki rigged, they might be closer to reality than are the current academic suppositions that East Polynesian voyagers had nothing better than the oceanic sprit.

In closeups the Moana waka seem extremely fast, as was the camakau above, and certainly they sail across the wind. They even do so rather recklessly, I think, manning and womanning large outriggers as if competing for the Polynesias Cup.

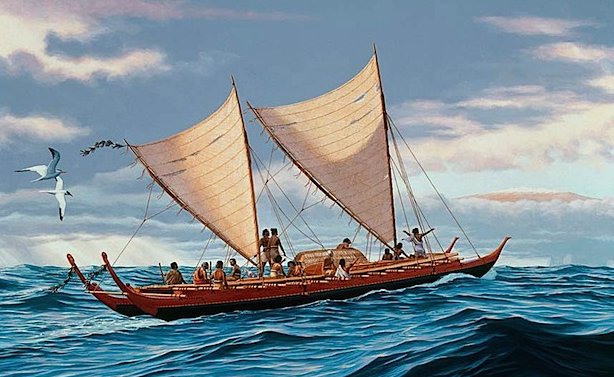

It’s generally held by academics that East Polynesians in pre-European times used only two spars to support each sail, one of which functioned as a mast. Here is a Herb Kane painting of a double waka with two such oceanic spritsails.

When working reconstructions of such polynesian voyaging canoes were built, beginning with the Hōkūle‘a in the 1970s, they often used two of these spritsails, as does New Zealand’s Te Aurere shown below.

When working reconstructions of such polynesian voyaging canoes were built, beginning with the Hōkūle‘a in the 1970s, they often used two of these spritsails, as does New Zealand’s Te Aurere shown below.

This rig seems to have many modern influences. Each ‘spritsail’ has effectively a separate mast onto which one of the two spars has been secured.

This rig seems to have many modern influences. Each ‘spritsail’ has effectively a separate mast onto which one of the two spars has been secured.

The one large double waka Cook encountered in New Zealand wasn’t rigged this way.

It looked like this. We don’t know if these spars crossed at some point or not. It doesn’t look that way, but tests have shown an oceanic spritsail works better if they do.

In this, an actual Maori sail Cook collected here, they might have crossed, perhaps as indicated here, or they might not. But could a sail and spars like these have sailed across the wind? This seems more like a temporary rig that you could keep in place with ropes to catch a following wind and very little else.

Lets look now at the smaller waka which Moana sails herself. It’s sail definitely isn’t used here as an oceanic lateen or tongiaki rig – instead in this configuration it appears to be a modern oceanic spritsail.

And it’s quite versatile; see it racing here, apparently across the wind, with Maui at the helm.

And here we see that like the other waka in Moana this one has a fixed and fork topped mast.

But a mast mounted at the front, not centrally. So if the upright spar was lifted from the mast and then suspended at a central point from the mast’s fork, and if the ‘tack’ where the spars meet was held against the prow this rig would almost match those of Moana’s other waka as seen earlier. It couldn’t shunt, because the mast is at the front, but set up that way it would certainly suggest the tongiaki rig.

But a mast mounted at the front, not centrally. So if the upright spar was lifted from the mast and then suspended at a central point from the mast’s fork, and if the ‘tack’ where the spars meet was held against the prow this rig would almost match those of Moana’s other waka as seen earlier. It couldn’t shunt, because the mast is at the front, but set up that way it would certainly suggest the tongiaki rig.

In Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand it’s suggested that New Zealand’s Polynesian settlers came in a substantial fleet from a ‘Hawaiiki zone’. This zone included the Cook Islands, which as Triangular Men suggests was well within the zone known to the tongiaki waka of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire.

In Mass Migration the authors go on to say: “this was a planned migration, based on prior knowledge of the location of New Zealand, and it involved a number of interacting communities within a zone of regular interaction in central East Polynesia. Not only was the migration planned and led by capable leaders, but the colonisation of New Zealand itself was efficient and rapidly executed. The essential strategy of the colonists seems to have been to reproduce the social and economic structures of Hawaiiki in the new land. As in tropical East Polynesia, this involved the establishment of a communication network linking communities on an expanding colonial frontier. … Archaeological investigation will probably never tell us about individual motives, ideological drivers or the role of visionary chiefs in the migration and colonisation of New Zealand. But these are precisely the issues that oral tradition addresses and it is now time to take a more nuanced and critical look at these traditions in order to further our understanding of migration, colonisation, and the relationship between early New Zealand and Hawaiiki society.”

The fleet is back. Moana will not be at all surprised.

thanks for the great images. The map of Polynesian would seem to be outmoded with the latest DNA evidence that shows Remote Oceanians are more closely related to Ontong Javanese, Sulawesi, lowland Philipines tribes, and Tongan and Samoan are lest related of the Pacific people due the fact that they were insitu for a at least a millennium before they migrated across the Pacific to Tahiti and from there to Rarotonga, Aotearoa to the west and Margusas and Hawaii to the north.

I wonder what is the meaning of the rooster drawn on the sail. that puzzles me

kia ora Keletaona — will try to find out more, and will get back to you.

Ngā mihi, Penny

Update (16 July 2023) — Unfortunately Te Papa (Museum of New Zealand) hasn’t yet replied to my query. I will keep trying. Penny

Great read, been getting obsessed with everything Polynesian in the last few years, especially the voyaging.