Robert Jenkin wrote:

After reading the 2007 New Zealand Book Award History prize-winning book Vaka Moana (2006, K.Howe ed.) and Atholl Anderson’s chapters of the 2015 Royal Society of New Zealand Science Book prize-winning book Tangata Whenua I think I understand that stages in the evolution of the shunting oceanic-lateen were first the double-sprit, next the oceanic-sprit, next and crucially the prop-masted oceanic-lateen, as used by Tonga in her ‘imperial’ period, which may have reached the Cook Islands from Tonga in or before the 11th century, and finally the shunting oceanic-lateen. This is the ‘flyer’ type, which so impressed visiting Europeans, first Magellan in Guam in 1521, then the Dutch in Batavia Java, in the 17th century and later the English and the French in northeast Polynesia in the 18th century. The shunting oceanic-lateen arguably out-performed any other sailing rig in the world, but in order to tack by ‘shunting’, waka that used it needed to be double-ended.

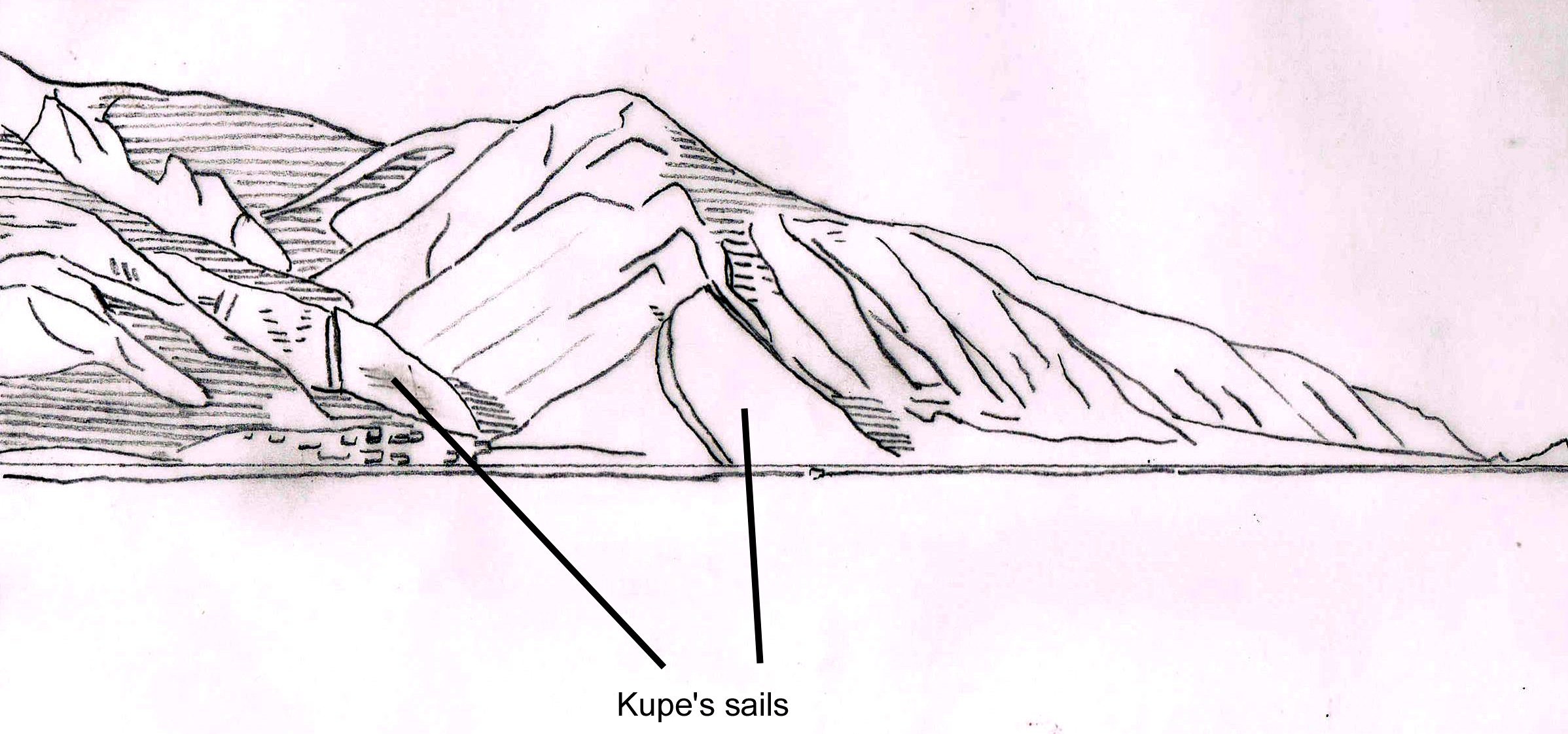

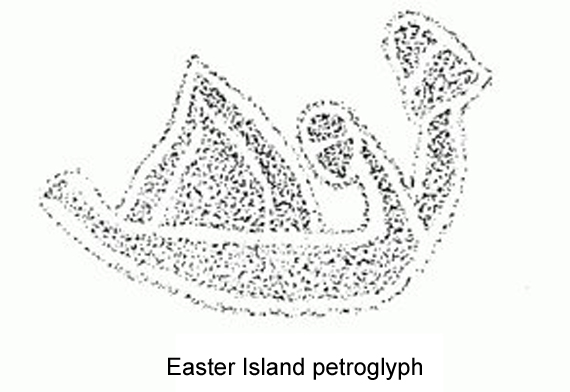

In order to to make return trips to South America, Easter Island, Hawaii and Aotearoa, East Polynesian voyaging waka had to sail fast, at least with and across the wind. The sail used on some of the voyaging canoes that came here in the thirteenth century could possibly have been the prop-masted oceanic-lateen, as indicated by the Wairarapa coast landforms called Kupe’s sails and also by an Easter Island petroglyph. This was also the sail first seen by Europeans on an open ocean voyaging canoe. The Schouten and le Maire expedition sighted, captured and eventually released a Tongan double hulled voyaging canoe with a complement of about 25 possibly on its way from Tonga to Samoa in 1616. Tonga and Samoa may have first developed prop-masted lateen sails centuries before, perhaps even before the 11th century. In that case East Polynesians would very possibly also have acquired them, perhaps through the Cook Islands, and used them in the the 12th and 13th centuries for their far-ranging trans-Pacific voyages.

In order to to make return trips to South America, Easter Island, Hawaii and Aotearoa, East Polynesian voyaging waka had to sail fast, at least with and across the wind. The sail used on some of the voyaging canoes that came here in the thirteenth century could possibly have been the prop-masted oceanic-lateen, as indicated by the Wairarapa coast landforms called Kupe’s sails and also by an Easter Island petroglyph. This was also the sail first seen by Europeans on an open ocean voyaging canoe. The Schouten and le Maire expedition sighted, captured and eventually released a Tongan double hulled voyaging canoe with a complement of about 25 possibly on its way from Tonga to Samoa in 1616. Tonga and Samoa may have first developed prop-masted lateen sails centuries before, perhaps even before the 11th century. In that case East Polynesians would very possibly also have acquired them, perhaps through the Cook Islands, and used them in the the 12th and 13th centuries for their far-ranging trans-Pacific voyages.

Later and smaller paddle-powered and sail-capable waka subsequently used in East and South Polynesia for shorter coastal or inter-island trips often reverted to using one or more oceanic-sprit sails. Though some East Polynesian peoples went on to develop the shunting oceanic-lateen, perhaps through their continuing contact with West Polynesia, Maori did not. Instead, by making use of larger trees than were available elsewhere, they started making waka broad enough of beam to manage open water coastal voyaging with single hulls, but in a single hull without an outrigger you had to use a double-sprit or oceanic-sprit. A single hull with any kind of lateen sail and without an outrigger would certainly capsize.

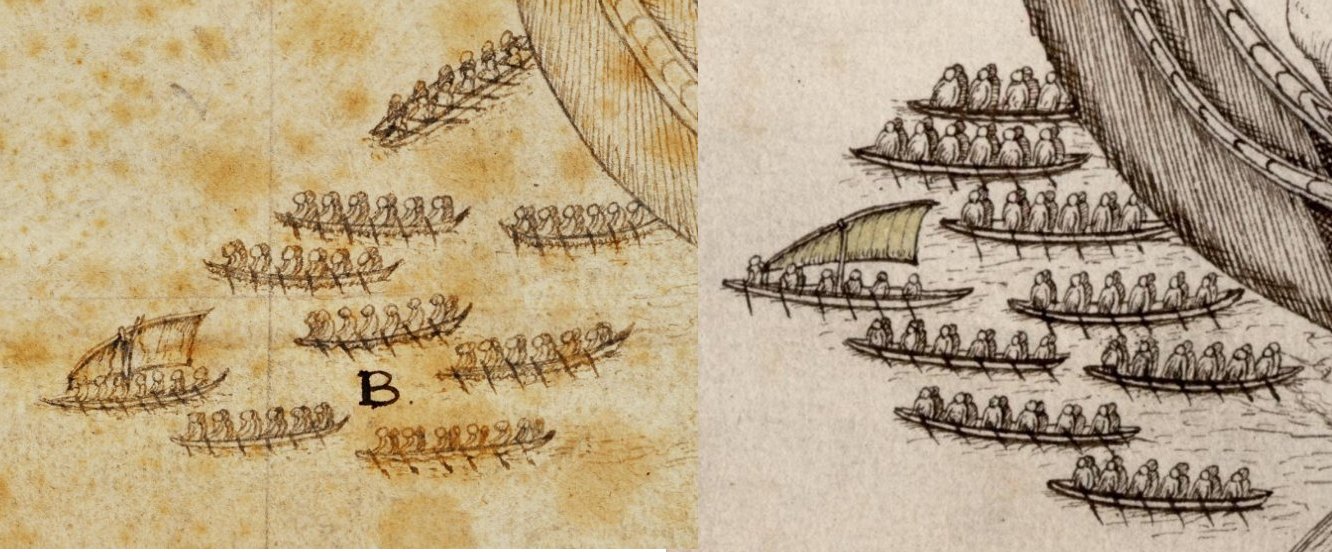

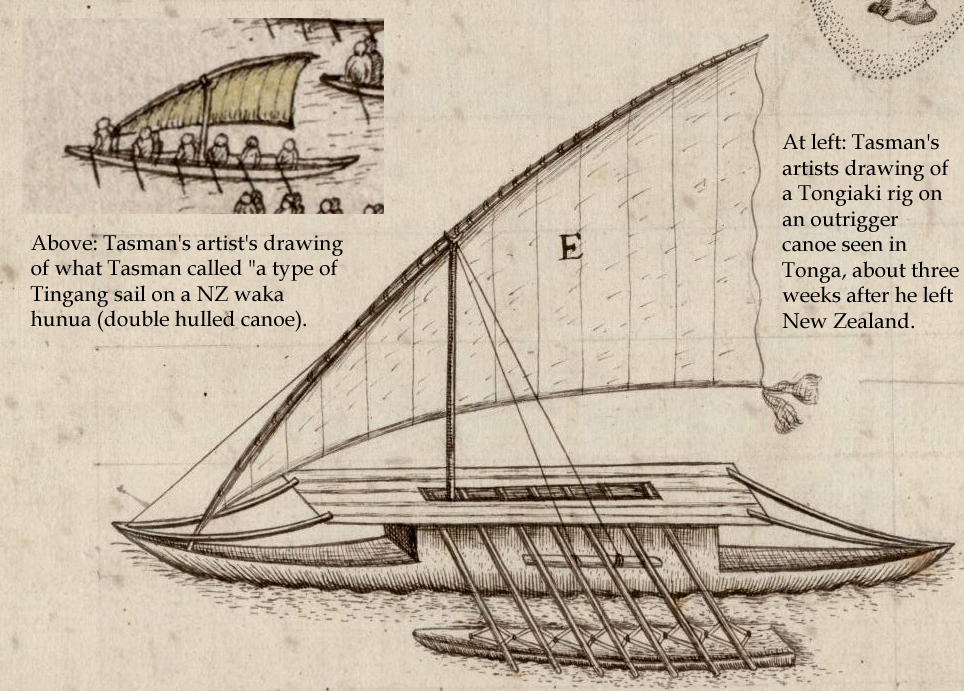

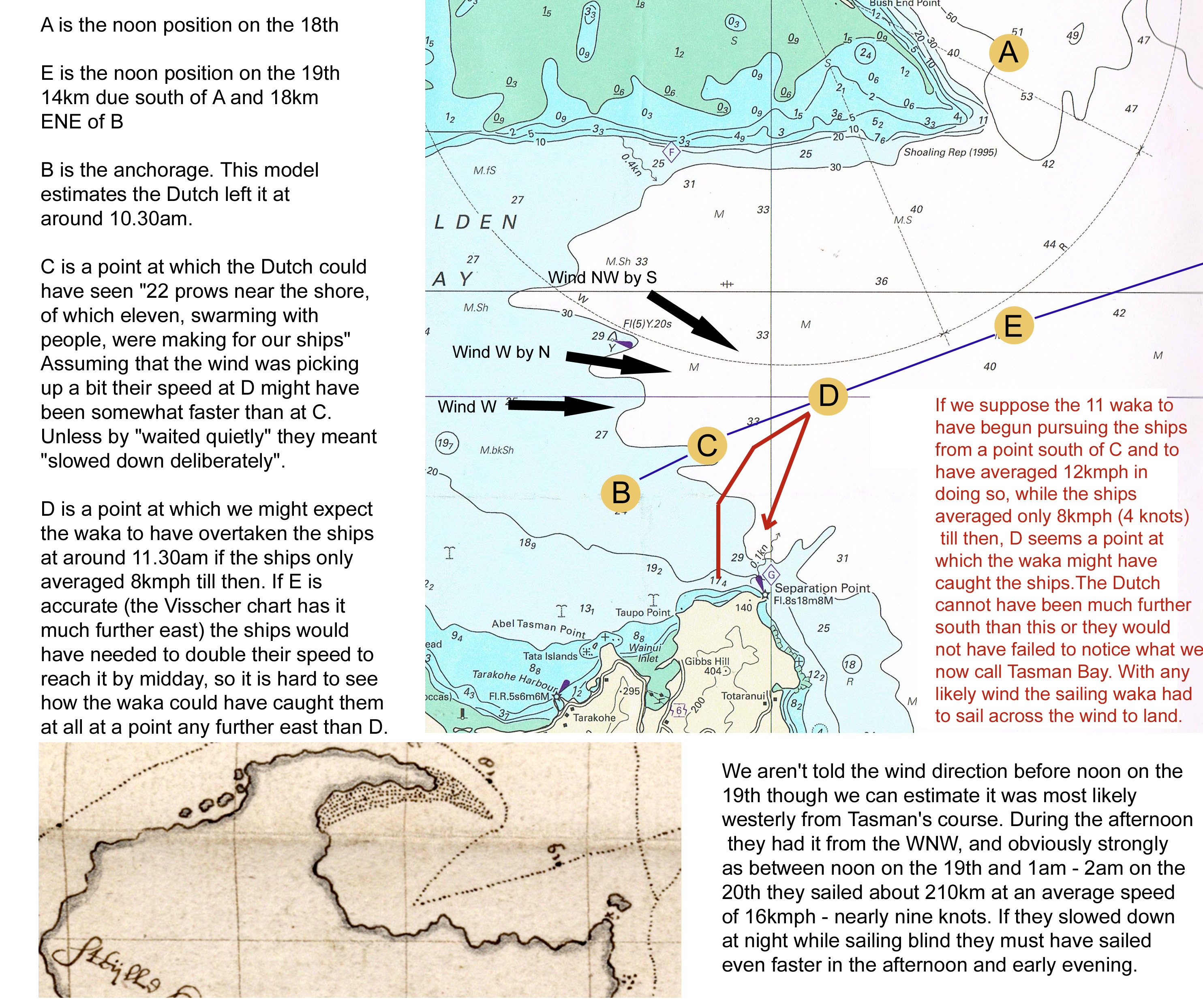

Perhaps Aotearoa waka had an intermediary phase between the use of prop-masted oceanic-lateen rigged double hulled large voyaging canoes, some of which, like the the ‘Anaweka Waka’ were built locally, and broad beamed single hull waka tete and waka taua. Perhaps during this phase some smaller paddle-powered and sail-capable double hulled waka did carry prop-masted oceanic-lateen sails, and two of these were noted and recorded by Tasman’s expedition. About an hour after the killing of at least three Dutchmen in an attack on a Dutch small boat a fleet of eleven double waka under paddle power alone pursued the Dutch ships as they sailed ENE past Separation Point. The Dutch fired on them, after which they all turned back, two raising sails and sailing SSW across or even a little into the wind back towards land. The wind was probably from the W or WNW, allowing the Dutch a broad reach, their fastest point of sail. Tasman compared the sails Maori set to oceanic-lateens used by Javan ‘tingangs. Two illustrations made by those involved later in 1642 appear to show the sails seen as prop-masted lateens.

Two illustrations of a Maori sail seen in Golden Bay. Both seem to show a prop-masted oceanic-lateen

Oops, I meant this to be open for comments. It is now. And I will comment first:

Naomi Arnold wrote in 2012: “Tasman might not have been the first European to sight us – just the first to make it back alive.

“These people were extravagantly fond of nails above every other thing,” Captain Cook wrote in his diary on November 2, 1773, bobbing about in Queen Charlotte Sound. Three years earlier, when he’d first encountered Maori in the sound, they’d asked for whau, or spike nails – a commodity so valuable that it has its own index entry in Hilary and John Mitchell’s stunning local history, Te Tau Ihu o Te Waka.

How did Maori know to trade for nails with the first Europeans to make their acquaintance? What other explorers or seafarers had met them before, but failed to return with the news? What other secrets lie buried at sea?”

http://www.stuff.co.nz/nelson-mail/opinion/columnists/naomi-arnold/7284557/History-made-and-lost

Naomi seems completely unaware that Maori also got around (which I see as the glaring error in the current and received narratives regarding Tasman’s visit) Naomi assumes that while Cook sailed slowly round the ‘North Island’ stopping off frequently along the way, Maori just stayed wherever they had happened to be ‘found’ by Europeans. In fact waka borne Maori had plenty of time to get ahead of Cook and take his nails and the news of their uses and how to aquire them to Queen Charlotte Sound well before Cook got there.

Dutch Europeans, grand seamen with evolving maritime technology, meet Polynesian colonists not long established on these shores (a mere 400 years) also grand seamen with evolving maritime technology. Both have a long tradition of open sea voyaging, although the Polynesian one is longer, having started well before the Portugese.

Tasman is chased out of Golden Bay by fast fierce heavily manned catamarans. Their owners have already killed or captured four of Tasman’s men right under his supposedly intimidating guns. These ‘natives’ had first seen and heard these at their most unexpected and intimidating (i.e. unexpectedly in near total darkness) just the night before, but very clearly weren’t cowed or overawed.

Then, after having a good look at the Dutchman they had taken back to shore (or at least closer to shore, as we don’t know whether they went all the way back to land or just back to a main fleet somewhat closer to land) Maori decided for whatever reason to pursue the Dutch, who were by then hightailing it away from ‘Murderers’ Bay’. It was a hot pursuit. The natives quickly overhauled their quarry under paddle power alone. These were the waka hunua Matahi Whakataka Brightwell called ‘torpedoes of our canoe culture’. A Maori in a leading waka then held up a peace emblem, the same sort of white emblem that the Dutch had waved at Maori waka only hours before. No wonder this is not a story often told by the colonialist historians. Which of these cultures shows, at this junction, the greater agency?

However, after being pelted with stones from Zeehaen’s modest stern-chasers, (hardly a conciliatory response) the man with the white emblem either falls or ducks. To me the pursuit up to this point possibly indicates a willingness on the part of Maori to reconsider their previous inscrutable hostility. Or was it possibly a cunning plan to kill or capture all the strangers and their wondrous ships, a plan that could even have been within their power if there were over 300 of them in these eleven waka as Visscher’s report cited in Witsen seems to indicate (Mack, 2006, p.77); After easily overtaking the Dutch vessels they might well have outmanouvered the Dutch yet again, got in under the guns, run up the sides, and outnumbering the then surviving Dutchmen by more than three to one, carried the day. This possibility and all the circumstances that relate to it is or I think ought to be the climax and pivotal moment of the whole narrative.

Instead, with no further demonstration of any kind, the eleven pursuing waka broke off their pursuit and rejoined the other half of their fleet. Perhaps what they had wanted really was to parley: on the night before they had responded to cannons with something like a haka; this time they just turned round and made their way (in what may well have been deteriorating weather, from their point of view) straight back to shore. They evidently saw no need to signal their defiance once again. Two waka now set sails which Tasman’s journal says were like tingang sails.

Now this is getting seriously interesting.

The ‘tingangs’ of Batavia (‘flyers’ as the Indonesian Dutch often called them) were double ended shunting craft with oceanic lateens, judging by 17th century Dutch pictures I have found. The sails seen by Dutch on Maori waka must have been in some ways similar, though Tasman’s artist’s, especially in the Blok illustration, suggest the lateens used by Mori had crutch masts, as shown above.

Did Tasman’s unknown artist/s base these on the masts they later saw in Tonga? Like Wallace (2006), I have considerable faith in Dutch marine artists’ documentary drawing skills, so don’t think that. They had no reason to suppose Tongan and Maori craft would be alike, and overall they certainly proved not to be. And isn’t it more probable a sketch or sketches of these Maori sails were made before the expedition got to Tonga anyway?

I can agree with Geoff Irwin that Maori may have used the oceanic sprit to get here (and lets agree with Atholl Anderson in ‘Tangata Whenua’ that they arrived here in the 13th century) in vessels like the Anaweka waka. They must have kept on using waka of that type (according to the carbon dated caulking of the Anaweka waka anyway) for at least one more century and maybe two or more. The Anaweka waka was a voyaging canoe, capable of extended ocean voyages.

Similarities between models of Cook island waka and the Maori waka seen by Tasman, especially in the overall style and decoration, suggest to me ongoing contact between Aotearoa and those islands prior to 1642: the waka enlarged by Tasman’s artist is reminiscent stylistically of a similar size of waka hunua that is known from the Cooks as some survived into the 19th century and were photographed, having remained useful for putting out nets. For such a use their hulls were obviously lashed further apart.

It seems that shunting waka with forked masts developed from the crutch mast Tongiaki type, where the upper spar was hauled up to the crutch rather than cradled in it, and were in use in the Cook Islands circa 1700 – 1800. In centuries before this I assume they also sailed non shunting types.

To me the currently most interesting question about Tasman’s visit is whether Dutch pictorial and textual evidence does argue, or supports an argument, that Maori were or had been in contact with the Cooks perhaps not longer than two centuries before.

Many features of Maori and Cook Is. waka suggest to me a period of co-evolution or at least co-influence. And then there is the possible involvement of the Tongan Empire. When will we stop assuming Maori were just doing nothing much and waiting to be found by Europeans?

Our 1642 ‘first contact’ story is not one in which agency is easily assigned only to Europeans. They came, they saw, they were well and truly outmanouvered, and then they rapidly cleared off again, for nearly 130 years. And I would say that Cook, without Tupaia’s benign agency, could well have had a similar or even worse experience.

I’m not arguing that Maori were technologically or numerically in any position to hold off a sustained European assault, though Belich does argue something along those lines in ‘The NZ Wars’. What I am arguing is that colonialist narratives tend to deprive non Europeans of equal agency, meaning the power to shape events themselves.

Words like ‘tragic events’ have been applied to Tasman’s visit, as if it were all an unfortunate misunderstanding or an unlucky accident. I see it as two cultures in violent collision, and, as I wrote in ‘Strangers in Mohua’, I see its overall outcome as beneficial for Maori, since 19th century Brits were more ‘enlightened’ than 17th century Dutch.

“Radiocarbon dating, carried out by three separate laboratories, two in New Zealand and one in the United States, all came in at between 1226-1280 AD for age of the timber, and 40 or so years later for the caulking material. The PNAS authors concluded from the last caulking and repair dates that the last likely voyage of this waka was around 1400 AD.”

Just want to say thanks for your work on this. I’m enthralled! That turtle!