Contemporary illustrations of past events can and do complement written history, and much may yet be learned, as Patricia Wallace has shown in her 2006 article ‘Traditional Maori Dress: Recovery of a Seventeenth–Century Style?’, from illustrations that appear in the State Archives Copy (SAC) of Tasman’s Journal.

As Andrew Sharp explains in The Voyages of Abel Janszoon Tasman, the SAC, which still bears Tasman’s signature, is likely to have been one of several “day registers of the aforesaid Tasman” that were consigned to the Netherlands from Batavia and mentioned in a V.O.C. report dated 22 Dec.1643. Sharp further comments that the SAC illustrations were “evidently drawn in in spaces left for them in the text” and that our two surviving journal texts, SAC and Huydercoper, are “independent copies of the same [now lost] original journal”.

We therefore have sound provenance for SAC; we know its charts and illustrations were produced by V.O.C. employees in Batavia in 1643, and may presume they were derived from originals created on Tasman’s 1642-1643 expedition, since he himself authenticated them by signing them.

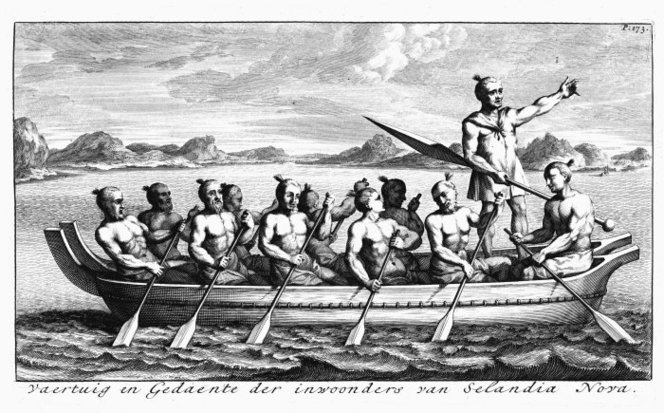

Problems may well occur if later illustrations that apparently derive from SAC are thought to be a source of further data not contained in the originals, and so a valid basis for new written history. Such problems plague an article by Rudiger Mack, ‘Did Dutch Sailors land in Wainui Bay on 18 December 1642: The First Printed Illustration of New Zealand’ ( 2004 Turnbull Library Record (TLR) 37, 2004) which seeks to overturn existing Tasman history on the authority of Vaertuig en Gedaente der inwoonders van Selandia Nova (Vessel and appearance of the inhabitants of New Zealand’), a plate commissioned by Nicholas Witsen to illustrate his 1705 work Noord en Oost Tartarije.

Mack is presumably aware that to present an engraving that postdates SAC by 62 years yet seems to be derived from it as a new historical source will challenge the credulity of some. This may be why he frames the source of his revisionist hypothesis as “The First Printed Illustration of New Zealand”. While technically this is the case, why is its ‘printed’ category relevant? Whether a page is printed or hand-drawn does not affect its primacy. What matters is that ‘Thus appears the Murderers Bay when you lie anchored in 15 fathoms in it’ was published in 1643, while ‘Vessel and appearance of the inhabitants of New Zealand’ was published in 1705.

But Mack apparently regards the later illustration as the better drawn: “The Witsen illustration has been engraved by a skilled engraver. This is obvious when looking at and comparing some details, e.g., the head of the second person from the left. In the SAM and BF illustrations his head appears far too big. Likewise the head of the Maori standing at the front appears to have the wrong proportions; and the double canoe looks very much overcrowded with very little space for the paddlers. In the Witsen illustration, the standing man’s head, and the proportion between the size of the canoe and the size of the paddlers, are much more realistic”(Mack, 2004, p.16). And from this argument he goes on to suggest the later image has greater authority.

There is another and perhaps a better way of understanding the apparent differences. In 1667 André Félibien helped to anticipate the important ‘history genre’ of art that became dominant in the 18th century in these words: “as man is the most perfect work of God on the earth, it is also certain that he who becomes an imitator of God in representing human figures, is much more excellent than all the others … history and myth must be depicted; great events must be represented as by historians” (click here for link).

Seen in this light it isn’t hard to understand how six decades after Tasman’s illustrator produced ‘Thus appears the Murderers Bay‘, which Mack describes as “Wainui Bay from a bird’s-eye perspective” (p.15), Witsen’s illustrator adapted it into a more ‘perfect’ image that would appeal more to Witsen and to Witsen’s readership through its compliance with contemporary artistic norms.

One way of doing that was to ‘improve’ anatomy, as Mack observes. Another was to introduce more light and shade for greater depth and drama. Another was to flatten the horizon; Wallace explains that ‘bird’s eye views’ were often used in 16th and 17th century illustration, citing the influence of Saenredam, Vroom and van Wieringen (Abel Tasman 370 Seminar, Summary Account of Proceedings, p.4). However by the 18th century this way of drawing was no longer very often used.

It’s fairly clear from well informed examination of both texts that ‘Thus appears the Murderers Bay when you lie anchored in 15 fathoms in it‘ ‘belongs’ to 1643, while ‘Vessel and appearance of the inhabitants of New Zealand ‘belongs’ to 1705. The altered, largely horizontal landscape of the latter is conventionally 18th century, as are the added waves below the waka and the added clouds above. Surely the simplest explanation is that the engraver used artist’s license in reinterpreting the 1643 illustrations on which the five new plates were based, according to conventions of his time.

Nowhere in Mack’s three articles is such a possibility addressed. Instead he writes: “When were the canoe and the coastal landscape shown in the Witsen illustration sketched?”, and answers this with a new theory, flatly contradicting Tasman’s own account as found in SAC and Huydercoper manuscripts and unsupported by two other extant eye-witness accounts of events in Golden Bay, Haalbos/Montanus and the Sailors Journal (Sharp pp.41-42, pp.276-277).

Mack’s theory is that tiny details, ‘marginalia’ as it were, in the engraved adaptation, details “not visible at a first glance”, as he himself acknowledges, which “need to be studied with a magnifying glass or a powerful scanner” (Mack, 2004, p.18) support a prima facie case that the 1705 Witsen engraving is more historically accurate than is the hand drawn 1643 illustration which other commentators and even librarians regard as the original (e.g. Collins, 1991, p.11; Tapuhi: “Derived from … ‘View of Murderers’ Bay’ from Abel Tasman’s journal” click here for link).

Mack goes on to conclude that Tasman’s scouting party “came as close as 50 metres from the shore at the northwestern point of Wainui Bay, and there is a strong possibility that one of the Dutch boats landed at the Taupo Point beach some 127 years before Cook’s men landed near Gisborne” (Mack, 2004, p.25).

There are many and varied objections to this hypothesis, and Anderson (TLR 38, 2005) has dealt with some of them. Mack writes “It appears that Witsen had access to Visscher’s account of thc voyage (Sharp 346). Witsen’s illustrations should be regarded as equal in importance to the illustrations in the SAM [SAC], HM [Huydercoper manuscript] and BF [Blok Fragment]. The illustration of Wainui Bay shows more detail and is of a much higher level of craftsmanship, so the illustrations published by Witsen might bc considered superior.” As a response to this one might repeat that both are of their time and neither is superior. However, the contemporary drawings and illustrations made by the eye-witnesses might well be seen as more authoritative sources than later adaptations of them.

If for the sake of argument we accept Mack’s theory that Witsen’s illustrations prove the existence of other and previously unknown drawings dating from 1642 and 1643, which Witsen had access to because they were in Visscher’s now lost journal, though Visscher produced no other extant drawings, only maps, and while he was described by his superiors in 1634 as having “greater skill in the surveying of coasts and the mapping out of lands than any of the steersman present in these parts” (Sharp, p.27), it was Gilsemans who was described on August 1 1642 as having “fair knowledge of … the drawing of lands”; if as I say we set these doubts aside and go with Mack to a presumed scenario in which Witsen presents the new exciting evidence of Visscher’s Journal to his commissioned artist, we might imagine him as saying happily: “Now look at this! We Dutch really did land in that place called New Zealand after all! You draw a careful copy, showing how close our boats really got to shore, and I’ll go off and write to all my friends – isn’t this wonderful.”

That is the way that I imagine Visscher might have felt, and so perhaps captioned it as: ‘Dutch landing craft close to New Zealand shore’, though perhaps in an altogether different published work. But no, it seems we must imagine Witsen saying: “Show the inhabitants of New Zealand in their vessel up big and close, but don’t make the Dutch boat near the shore at all obvious in case somebody notices. I won’t mention it at all in the caption. And make the other proas on the shore as inconspicuous as possible.”

I understand that Witsen’s subject in this chapter was the native peoples, not the Dutch. Why then put any Dutch boats into it? There are none visible in any of the other four such plates. Why, if he really had compelling previously unpublished evidence of a Dutch landing in New Zealand, did Witsen never publish it or even mention it anywhere else? Mack doesn’t help with this, though he suggests that Witsen may have actually ‘deleted’ some explanatory text: “The Dutch boat shown might be a symbolic representation that was deprived of explanation when the textual clarification was deleted” (2004, p.24).

We have no extant Visscher diary, so cannot say with certainty what it contained. Since Mack has shown he is prepared to speculate, and to a large extent for academic written history, I’d like to hear him speculate on why exactly Witsen would delete textual evidence of a Dutch landing in New Zealand, if such came into his hands.

Witsen was a writer, a geographer, a lover of information. In 2012 Mack told me that the chapter of Noord en Oost Tartarije containing the five illustrations, which I can’t read, because it’s in old Dutch, “is about people in America, South-East Asia, Australia and the Pacific and whether they originally came from Asia.” (personal communication, 22.3.12). If Witsen thought that Maori came from Asia, then most historians will now agree with him. Since hearing this I’ve thought the Asian looking craft below, which Mack interprets as a Dutch open boat, is much more likely to be Witsen’s artist’s guess at a New Zealand boat. Till Mack explains why he thinks Witsen would delete importance textual evidence about what happened in New Zealand in 1642, I see his startling theories as an unprovoked attack on Witsen’s judgement and integrity. I also see Mack as misguided in interpreting the five 1705 SAC derived Witsen plates as providing any new evidence concerning the 1642-43 voyage of discovery commanded by Abel Tasman.

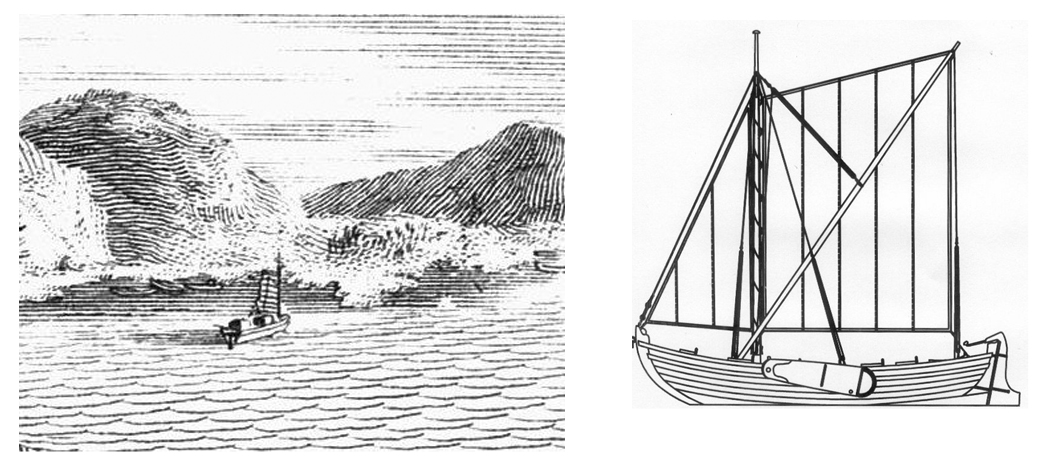

Witsen large boat near shore (left) and illustration captioned ‘Common sprit-rig as generally used on boats in the 17th century’ in ‘The Ships of Abel Tasman’, Hoving and Emke p.91 (right).

Mack writes of the above: “The boat is under sail and appears to be loaded with water barrels. … It has a common sprit-rig as generally used on boats in the 17th century (Hoving and Emke 91).

It’s being shown near a beach close to the Tata Islands correlates with the Ngati Tumatakokiri tradition that their first encounter with the Dutch occurred in this vicinity (Mack, 2004, p.21)”.

The oservations identifying the boat as Dutch are debateable: Hoving observes “as to the reference in Mack’s article to my book, I can hardly say I recognise anything I wrote there. The vessel certainly does not look Dutch with these horizontal drawn bars in the sail. It looks like reed or something? It’s an inland vessel in that case, I would say. Water barrels in boats were not transported up in such a high position as drawn in the picture, the boat would surely capsize. Something as high as that can only be explained as a sort of awning against the sun” (personal communication, 16.3.12).

The observation about Ngati Tumatakokiri tradition is equally debatable: Anderson writes “I know of no oral tribal history recording the event” (The Merchant of the Zeehaen, p.84). What Mack refers to as ‘Maori traditions of Tasman’s visit to Golden Bay’ (2004, p.25) are written reports by Europeans of what they claim that Maori said to them, in every case as answers to the leading questions Europeans had asked. The Banks account puts the encounter/attack in Queen Charlotte Sound, Mackay has it at Tata Islands, which are a little to the west of Abel Tasman Point, Smith has it at ‘Whanawhana’ (perhaps today’s Wharawharangi Beach) and Stephen Gerard’s Strait of Adventure chapter ‘The Wizard of Abel Tasman’s Roads”, far from preserving any “genuine trace-memory of the attack on Tasman’s boat-crew” as Mack suggests, is fictional and as its title shows mostly concerns supposed events near Admiralty Bay.

Tasman and Haelbos both describe the first encounter as some time after sunset and beside their ships. The sailor’s journal mentions no encounter until the 19th. On both those days the ships were anchored in about 25.5 metres of water (15 Dutch fathoms, if Hoving’s 1.7 metre Amsterdam fathom is applied), which means some 6km from land, possibly due north of Abel Tasman Point. Distance from land would lessen further east and lengthen further west.

Joan Druett’s take in her 2011 book ‘Tupaia’ concerning what was said by Maori informant ‘Topaa’ in Queen Charlotte Sound in 1769 is interesting:

“On 5 February [Topaa] came on board to watch their preparations for departure with half-hidden relief, to find himself cross-examined yet again, as Tupaia seized the opportunity to ask more questions.

Where had his ancestors come from? Hawaiiki, Topaa replied (spelled ‘Heawye’ by Banks, who was listening and taking notes as Tupaia translated) – the same Hawaiki Tupaia himself had described in stories and legends. Tupaia then asked if any ships like the Endeavour had called before. Though Topaa shook his head, he added that there was an old story of two large vessels, ‘much larger than theirs, which some time or other came here and were totally destroyed by the inhabitants and all the people belonging to them killed’, Tupaia apparently knew the story already, telling Banks that this was a very old tradition, ‘much older than his great grandfather, and relates to two large canoes which came from Olimaroa, one of the islands he has mentioned to us’.

…

Whether Tupaia was right, and Topaa’s tradition was an ancestral memory from before the settlement of New Zealand, or if, on the other hand, it referred to the 1642 visit of a Dutch two-ship expedition, commanded by Abel Tasman, it is impossible to tell. Banks was inclined to dismiss the story, remarking that ‘Tupia all along warnd us not to believe too much any thing these people told us’. It is even possible that Topaa was merely repeating one of the anacdotes Tupaia had already related.

As Cook commented, it seemed clear that no credence could be paid to this tale, as ‘there knowledge of this land is only traditionary’….” (pp.309-310)